March 11, 2019

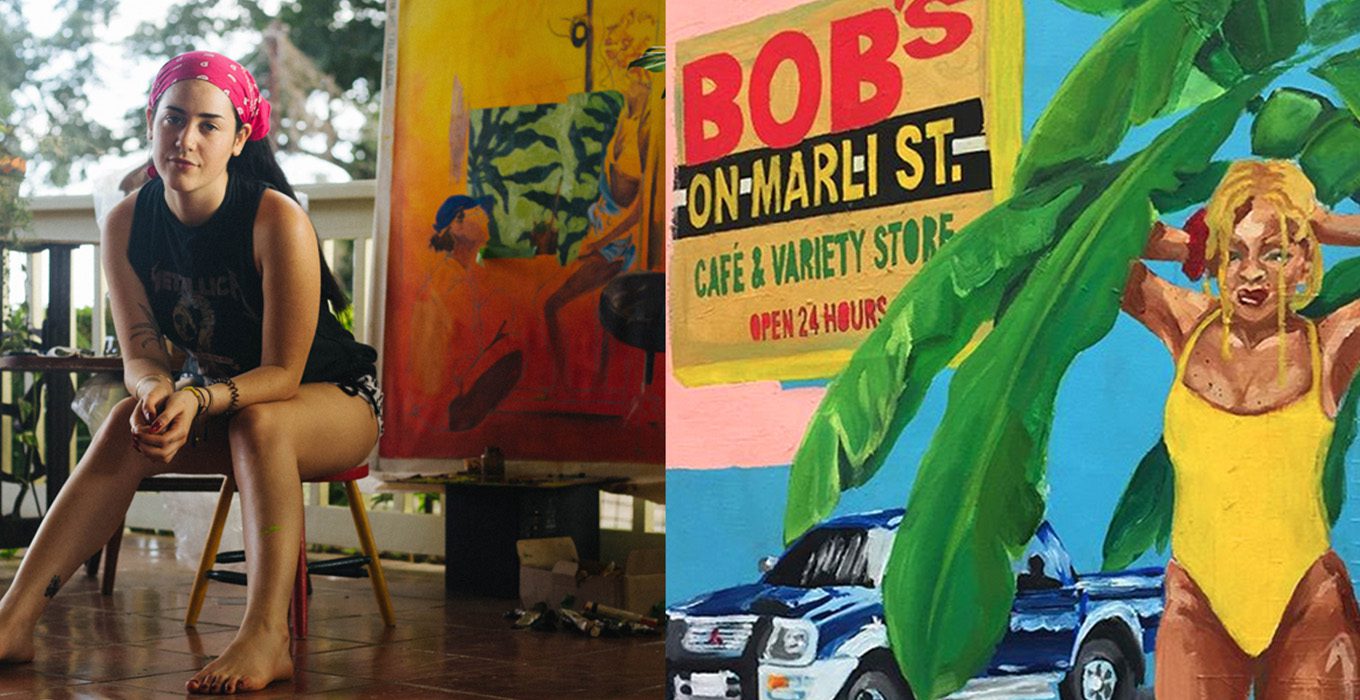

Twas the week before Christmas when we paid a visit to up and coming Trinidadian artist Bianca Peake. Nestled in her indoor/outdoor studio, we switched on our recorders and began to capture Bianca’s stream of consciousness, as she explored coming of age as an artist, honing her craft and telling the stories that matter to her.

Tackling the intricacies of being a woman and representing women in art and the politics behind it all. Navigating intercultural spaces, balancing passion and making a living, personal gratification and using art as a tool to transform lives and spark social change.

Here’s a sneak peak into the inner workings of the woman who brought us ‘The Signs of the Times’ exhibition and the “Not Yuh Gyal” street art and merch.

I give you Bianca Peake.

Elevator pitch who are you and what do you do?

BIANCA: I am Bianca, and I guess I’m that catch-all phrase ‘creative’. It’s cringy. I feel like everyone is a “creative” nowadays. I call myself a painter, but I have a background in other media and don’t like limiting myself. So I guess a creative is what you’re gonna have to say. Or maybe fine artist. I like that; it carries a certain intent with it.

What formative experiences led you to art?

BIANCA: I’ve always been creative. I wanted to be a writer when I was younger, but words can never fully express what’s happening inside. So I sought to bridge that gap, to find different ways of expressing myself and drawing just came naturally. I drew constantly but never took it seriously until my last year of secondary school. I was going to do psychology, and then I just woke up one day, and it hit me, ‘NO! You need to do something in art!’ It was that kind of epiphany moment. ‘No, no this is a mistake you need to do art, and it’s going to be hard, but you need to do it.’ So that was a turning point. All I had to do was convince everyone that art was a viable option, which is something that continues till this day- if it’s viable.

It gives me so much satisfaction. I like seeing something come from nothing. There’s nothing here, and now there’s something, and I made it with my own two hands. That sense of pride that this comes from you even if it’s shitty or whatever. That sense of pride is what I am chasing all the time. I may have all these faults in my personality, I may not be where I want to, but when I die at least, there’s this. A legacy almost. A physical, tangible thing. It doesn’t always live up to what I am trying to say, but it’s a manifestation of that, a fragment. It’s something bigger than myself, but it’s also really personal.

“No, no this is a mistake you need to do art, and it’s going to be hard, but you need to do it.”

Who or what inspires you?

BIANCA: Growing up I felt like a voyeur. Not in a sexual way. I was very anxious, and it’s something I’ve been working on throughout my life. I just felt like an observer, like an outsider looking in. I wasn’t really an outsider, but that’s how I felt. I would just watch life unfold around me and when you pay attention like that you pick up on the little things. I like zoning in on stuff in the background. I mean that happens with photography as well, photographers do that where you see the whole scene and then you zone into this one aspect that is interesting. It might not be interesting out of context, but when you cut the frame around it, it becomes something. It’s things like that that inspire me, but it’s also things people say: words and text.

“I am always trying to translate text into my work. Phrases are significant because they bring a sense of humanness.”

Little things can have such a heavy and metaphysical meaning. You can take something said in passing and make it metaphorical for your life. I’m a romantic, so I make everything dramatic! Someone could say something that is entirely out of context and, ‘Oh my gosh, that is a symbolisation for this or that’, and I’ll go on with it. That’s maybe not what they meant, but that’s what I took from it.

When it comes to actual art and painters, my favourite painter is Njideka Akunyili Crosby. She’s a Nigerian-American painter. (Obviously, I look at artists from Trinidad, and I think it’s important to stay in touch with everyone here and the work that they’re making.)

I saw Njideka’s exhibition Portals at the Victoria Miro Gallery, London in 2016 and it was life-changing. She makes these HUGE paintings, maybe 7 ft. by 10 ft. They explore her experience of intersecting identities, feelings of being in between America and Nigeria, incorporating all these interweavings of pop culture in Nigeria and the kind of fabrics that they use. She utilises a lot of image transfer, embedding the things that have impacted her throughout her life and then paints on-top of those layers, forcing you to look into the piece. As an observer seeing these things, you’re not from the culture and don’t necessarily know, but I relate to that feeling. It was something that I could transpose onto Trinidadian culture.

The exhibition was critical for me to see at the time because I had just gone to England and I didn’t know what kind of work I wanted to make. Before then I thought that Trinidadian art was cliché and I didn’t want to make it. It was this kind of idyllic thing, and I felt I needed to be something else.

Her work was so impactful, she was true to where she was coming from, but it was also true to the idea that she felt between these two places, living in these nonexistent plains of existence she was creating. While I feel like I can’t completely relate, I believe my experience has been similar living in England. That’s how you feel when you’re not at home; you’re in between places, you feel that tension.

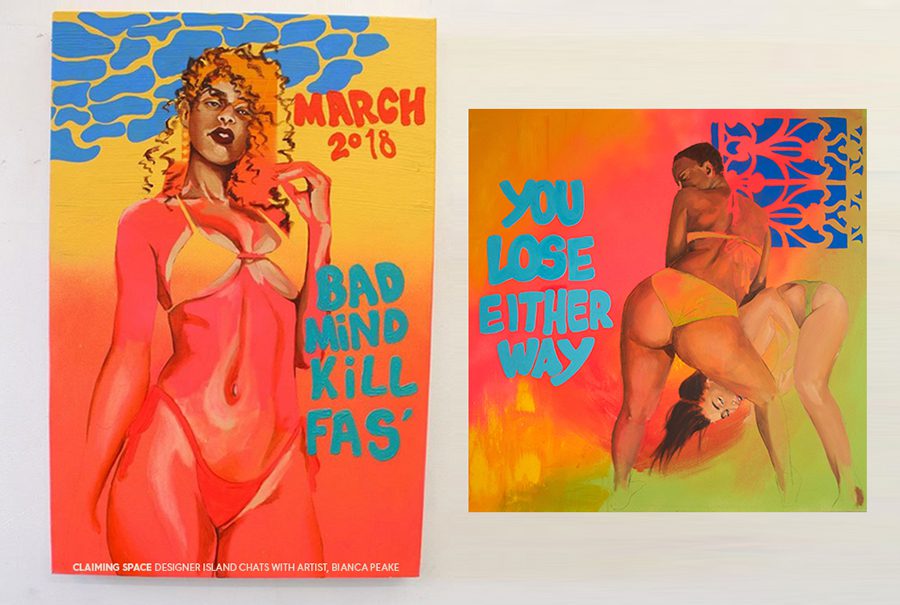

Tell us about your ‘Not Yuh Gyal’ series.

BIANCA: It came from a place of feminism. Now the phrase has blown up; it’s something you see on hats and all that. I’m pretty sure I was the first one to do that but anyway you know how Instagram culture is, no one owns anything. I started with this little design of two girls, bumpa to bumpa, bending over. I had an English crit look at my work, and say, ‘You’re self-objectifying’, and I went into crisis mode. Am I subjecting myself to this? Am I self-objectifying?

It’s hard and heavy. It’s heavy because this is not my body I am representing, but theoretically, it is my body because I am involved in this.

“Is playing Carnival, playing mas, me not living up to my feminist values?”

I went down this tangent, and then I was like, ‘No, people are allowed to have their sexual autonomy. They are allowed to do these things and not feel like they need to protect themselves or that they are putting themselves in danger.’ It came from the American versions, ‘Not Your Baby, Not Your Girl’ and so on. I thought there’s no Trini version, so I came up with ‘Not Yuh Gyal.’

The ideas behind it are especially relevant to Carnival spaces, it’s almost like you sign a contract when you go into a fete, and ‘Yes you can touch me.’ The number of maneuvers you have to go through with your girlfriends in these spaces, ‘Stand in front of me and if a man is coming let me know.’ It’s a lot, but at the same time you want to have fun, and you shouldn’t be demonised for wanting to have fun.

Initially, it was just a poster and some stickers.

I also have a background in Graffiti. It’s easier to do it in England because at home I will hear comments like, ‘That’s Bianca dere painting!’ Trinidad is so small! Even though policing is better over there, you don’t have the time in Trinidad because people are going to know who you are.

I was experimenting with paste-ups and stencils. I was on this tangent of public art is important. I was visiting a lot of galleries in London, and they felt like such alienating spaces. A bit over-intellectual and elitist, particularly when it comes to the language of art, some of which I’ve adopted myself because I have to. So that’s where my head was at when I was doing this project.

I came home and put up my paste-ups and stickers around the Savannah, Ariapita and St James. Some of them stayed, some of them didn’t, and people pulled them down.

I did another set with, ‘No Entry Without Permission’. Those went outside of Fatima, funny how quickly they got scraped down.

I put those up and became curious about things you can use, as I was working with installations, and exploring the idea of putting 2-D objects in a 3-D space. But I was also thinking- moneyyy, we need to make some money. I put them on a few hoodies and on like two hats and sold them. They went well, but that’s not my business. Kudos to people who make clothes and merchandise, it’s stressful, and I don’t have the kind of mind to keep up with it. I made about 30 and sold all of them, and people were asking for more, but I insisted, ‘Dat dead, it’s done.’ If you didn’t get them then, they’re done.’

I liked that project, but I feel like I’ve put it to rest. I was coming from a more generic place, and now I want to go in a more personal direction, even though I am not personally putting myself in the work. I got frustrated with myself at the end of the year because I was making these grand statements about a general population, and I wanted to bring it back into myself.

Your work has no shortage of bootylicious women, what inspired this muse?

BIANCA: I think sexuality is something I deal with a lot in my work. In the last couple of pieces I’ve made, I’ve been veering away from that completely, but I think it’s always there — my tension, with my sexuality. I am fascinated by the sheer confidence exuded in party spaces that I feel that I lack or sometimes want to possess.

“here, I’m taking up space, I am using my sexual autonomy, I am weaponising my body.”

I don’t ever want to make my subjects into stock characters. I want them to be their own people; they’re not just for my puppeteering. But obviously, I work with figures, so you need some representative form when you’re creating an image. I want to have this charged image that’s almost shocking when you first see it, but when you look deeper into it, you can see different elements within. It may be sexual, but there are also parts of it that are not. Parts of it that ask questions of you as a viewer. You’re watching them, but they are also looking at you looking at them, which is a critical aspect of my work— the gaze looking back. The female gaze, whatever the female gaze is. I feel like we look at ourselves through the male gaze, even though we’re engineering the female gaze, it’s all through the male gaze. I sometimes push the male gaze so you can see what it is but also how you can repossess yourself within its confines.

Tell me about your recent exhibition at Idlewood- “Signs of the Times.”

BIANCA: That was so random. I came home and went to a Freetown concert at the beginning of summer, and Marcus came up to me and asked if I wanted to do a show at Idlewood. ‘I have no work here but let’s do this!’ I brought maybe two paintings from away, but I had nothing. I had about a month and a half to prepare. So besides those two, I made everything from scratch. I think there were about twelve pieces. I was frantic, to say the least, running around like a headless chicken.

I had never done a solo show before so it was a huge learning process; overwhelming but really cool. It’s weird to have so much attention on you in one space, but it’s also very validating. As an artist, I am constantly having battles with myself. ‘Are you for real, this is what you’re doing?’ Even if people are supporting me, I still doubt myself. You don’t want to be a struggling artist. It means so much to me to have something like that happen. There will be more in the future, but the first one is such a validation. ‘Okay, I am doing something right, people are here, people are interested and engaged, people want the work.’ It was a tremendous validation.

Someone told me I should do an artist talk and I had a couple of panic attacks about that. I did it, got a few difficult questions but I think it’s important for people to question you. You don’t have to justify your work to anybody because it is your work, but it’s important to know what people are thinking. It was good practice, but it was also really vulnerable being open to being questioned like that.

It was an impulsive, whirlwind experience but a positive one. However, it was pretty short, so ideally in the future, I would like a longer exhibition and in a different space. That space was good for the time being, but next time I want to grow and spread out.

I’m making things that are bigger, which isn’t always what people want. I sold almost everything at the show, but many people asked if I had anything smaller. That’s not the direction I want to go; I want to go bigger. A tutor of mine said something that stuck with me; women painters tend to make small work and men just spread themselves out and make these huge things.

I observe it in the studio all the time; of course, some girls paint big, but the people who paint the biggest are the guys. They take up so much space, and they don’t even realise they’re doing it. It’s such an extension of manspreading. I wanted to make big paintings because of that.

“I can have a big dick painting too!”

I like small work as well because you have to go in and inspect it. With big paintings, you can be easily fooled and easily impressed. I think that’s why a lot of male painters opt to do that—just saying there’s a lot of untalented men that paint big and get way too much fame. So yeah, I dig a bigger space to do bigger paintings.

And “Signs of the Times” was such a great fucking name, like well done. I still feel great about that title. I used to struggle with naming paintings, but now sometimes the name comes before the painting. The words became the prompt. I’ve become so obsessed with signs and how signs influence us, how pop culture shapes us.

I came up with the name when I made the flyer, and I did that maybe two weeks before the show. I didn’t have a name before then, my focus was, ‘Finish these paintings! Everything else will come after.’

I feel like my work is changing, in the last couple of pieces, yes there’s text, but it’s not as much of a focal point as it used to be. The signs are slowly unravelling. They’re there, but they’re abstracting themselves. There’s always going to be signs, but they’re just pulling apart and seeing how far they can be construed…So that was the ‘Signs of the Times.’

Tell me about some of your more recent work.

BIANCA: The piece with ‘You Lose Either Way’ was a significant shift for me. It deceptively seems like the old work, same colours, same signs but it’s different. It was inspired by another one of my favourite painters; she’s South African, her name is Lady Skollie. Her titles are amazing; one of my favourites is, ‘Kind of, sort of UNITED we stand: Pros and cons of competitive sisterhood’.

It’s the idea that we’re kind of there for each other, but we’re also competing with one another; competing for male attention, competing to no avail. You trick yourself into thinking this is what you want, but those desires don’t exist in a vacuum. You think, ‘I’m not doing this for attention’, but to an extent, you are because all your life you’ve been groomed to please men, to perform for men and being a woman becomes a kind of performance.

I was thinking about that, and how we interact with our friends, sometimes this energy comes out, and we’re all losers in the end. So the name of that piece was ‘CHAMPION BUBBLA’.

“There’s no champion bubbla; you lose, either way, there’s no winning.”

What do you want to use your work to do/say?

BIANCA: Again this is another conflict question because sometimes I think painting is useless. It’s narcissistic. Why am I doing this? It’s the most pointless thing in the world. Then other times it’s the most critical thing in the world.

“I think it’s the posture; you get to meditate. It is narcissistic because it’s self-exploration, it’s me trying to figure things out about myself and the world around me.”

I used to think my work needed to contribute to the broader society, to make these grand statements, it needed to change something. But then you’re trying too hard. If you’re being true, people will relate to these experiences somehow. If you’re speaking about sexuality and being a woman, all these emotions, people are likely to connect.

I’ve taken a lot of pressure off of myself by not believing my work has to perform this function in the grander scheme. Paintings are pretty pictures, but they’re intelligent, and I think making this work is essential because it helps people think. Exhibitions can be life-changing- I’m not saying that’s me, I don’t think my work is there yet. But the fact that it can happen shows that maybe it’s not entirely indulgent. It’s not wholly narcissistic because you can have that experience with a painting.

There’s a difference between seeing a painting online and seeing it in person. It carries a sense of revere about it. It’s this elevated object on a pedestal, and it’s going to last. I think seeing paintings in a digital age is important. Some say painting is dead, but painting is never going to die.

People are still going to have those intimate moments with paintings. I hope so at least. You know when you see those grand Botticellis, they take your breath away. It’s not always a positive feeling you’re feeling but just because it’s not positive doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile. So maybe that’s why painting’s important.

I have a long way to go on my painting journey. I’m not keeping at it to get to the point where people have these moments, and they think art is valuable, but it would be nice if that happens along the way.

So what’s next for Bianca Peake? After school what do you want to do?

BIANCA: I want to paint! I just want to be a painter. I don’t know how realistic that is. I am interested in curation as well, and I want to do a masters in curation sometime after, maybe not immediately. Curation can become an experience. I think it’s important for curators to be artists. You can make a show an experience rather than things on a wall, and that’s what I want to do.

Immediately after- I want to paint, but I also want to be realistic. I think I am going to try working in some galleries in London before I graduate. When I come back, I’ll probably work and paint at the same time. But the ultimate goal is to paint. Or do something that marries that. I don’t ever want to forsake my creativity. What would be the point to it all?

I feel like everyone has a crisis after they graduate. I’m not unique in that respect. I want to paint, and I’m going to find a way to make that work. I believe I can if I put in enough work and get the right support. It’s not an option in my mind to think otherwise. It has to happen. There is no other way. I’m still figuring things out, but I’m in a good place.

“My art is nowhere near what I want it to be, but I’m learning how to make it what I want it to be.”

INTERVIEWER: BETHANY MILNE PHOTOGRAPHER: JHL PERSPECTIVS