November 15, 2018

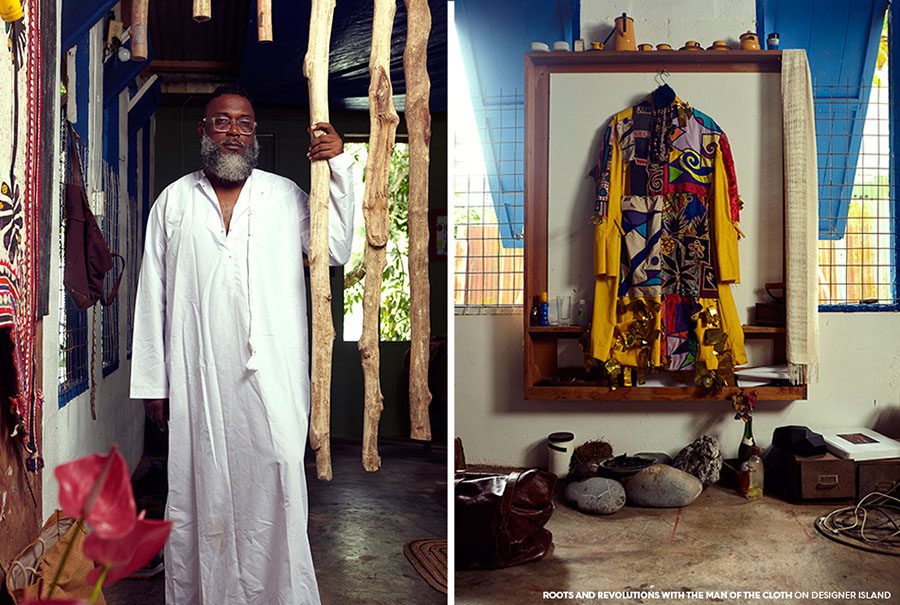

Once a vibrant space filled with makers and seamstresses and artists, the Maracas, St. Joseph birthplace of The Cloth is now a quiet space where founding designer Robert Young spends time reminiscing, reflecting and rejuvenating.

The brand, that has always been a consistent staple of the Caribbean fashion landscape, has been on the cusp of a reawakening…

Robert invited us in to understand the revolution that is The Cloth, his inspirations and influencers and to talk about where the brand is heading. — Join us on our journey.

This might be an unorthodox place to start, but coming out of the Meiling interview, she said, “Robert Young would be fantastic to interview because you would get so many stories.” So, can we begin with one of these stories?

ROBERT YOUNG: Well, up to last night, I was thinking of Christopher Pinheiro, because told me this story about how he got saved through colour. It was back in 1981, the night before the elections, and he was in the theatre on Pelham Street, right in Belmont there. That night the theatre caught on fire and he was sleeping inside. He survived but he was completely traumatized because it happened there in the theatre that he worked in and lived in. But he said he found himself – he got back himself – through colour. He started to paint dhoti shirts.

He, Claude Allum and Jeffery Stanford actually all started painting fabric around the same time. The two, Claude and Geoffrey, started a line called the D Village using silkscreen and hand-colour.

Christopher’s technique was different from theirs. He would fold the dhotis and do an ink blotting in plastic and then soak it and layer it and leave it to dry for days. The fabric would dry hard like a biscuit but when you peeled it apart you would see a repetition from the pattern from the top to the bottom. The top would be the darkest and brightest and the bottom would be the lightest.

Why am I telling you this? Because Chris was talking about designers who died. He said during Jouvert morning that year, as they passed the cemetery, they sang a song for John Isaacs from 3Canal because it was the 20th anniversary of his death. And before that, they were calling all the names of people who died. There were people like Jeffrey Stanford, Claude Allum, Junior Assevero, Junior Bristol, Petronella Alleyne, Chris Cooper, Lawrence Fredericks, Andre Burke…

Every time I think about it, it’s just sad. These were people whose work was much better than you could imagine. They just disappeared and you could hardly imagine what this space, Caribbean Fashion space, would have been. These were a whole set of men who, at that time, kinda created space for us to think about starting work.

Was that when you got into clothing design?

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes! That was when I started to see that clothes could be different.

I was going to pay a phone bill and I just decided not to pay it. Instead, I went to Singer and bought a sewing machine, and the first pair of pants I made was a skirt because I didn’t know how the frigging engineering works to make these things. That’s also how I met Christopher Pinero. I walked into his show at Normandie and he saw these walled batik pants, but he also saw the two lines in the crotch and that there was no zip, no buttons. I wore them anyways. 2017 was the 31st anniversary of that idea.

And from there?

ROBERT YOUNG: From there, the first show I did was ‘Hot Hot Summer’, or some foolishness like that. I’d been working on a collection of shirts for Karen Barrington who had a shop in St James that was selling local work. Again, just a hole in the neck, but interesting pieces and things. So, she said she wanted me to show, and supplied me with some fabric but all the things were dyed and they were polyester cotton so the dye didn’t hold – it was faint.

So, there was that… But at that show, I was working with Camille Selvon. She wanted to do some statement things, about

Mandela,

Cocaine,

Racism

And all ah that she painted – graphic images and protest things like you’ll see on the back of the TIWU T-shirts,

“United in Struggle,”

or like in Starliff steelband, “We, Not I.”

But those were small prints.

We eventually moved on to big t-shirts with big statements – anti-nuclear statements, because at that time there were tons of nuclear protests. People were marching into nuclear facilities and there was a lot of fear about the US and the USSR going to war. So a big part of our designs were statements about taking the US flag. And we took the hammer and sickle and the US flag and we made it into one symbol. We used that all the time on the clothes.

Now, a lot of our work would probably be seen as terrifying!

Was Camille always part of The Cloth?

ROBERT YOUNG: Well, there were three very interesting women to start: Camille, Adele Todd and Natalie Phillips. Camille said that there was a grant the government was giving out – this was in May and the elections were coming up in September, so they were trying to see what they could do for the young people. The grant was for $10,000tt so Camille and I started making plans.

I was working on a fashion show set for Junior Bristol in St. Joseph and met up with a guy called Addison La Platte. He said that if we were doing this thing, we should hook up with Adele who could really paint massive, very Japanese things. So I met with her and we started to work on this proposal.

Then Camille came and introduced us to Natalie and we applied for this thing, as The Cloth. We won the grant but the party in power lost the elections so we never got the money but we showed at an event called ‘Meeting Point’ with Meiling and Heather Jones. It was a whole show of new and young designers, kinda like a community group. My brother was part of it and the idea was that UWI St. Augustine was a meeting place of East, West, North and South. A lot of designers were involved and it was successful for about four years.

During the 80s and 90s, there were a lot of designers?

ROBERT YOUNG: Well, there was a ban on imported clothing because the foreign exchange was $2.42TT to $1US. You couldn’t even leave Trinidad without declaring your taxes and paying your taxes and then getting a travel document from the tax office. So people are beating up now but back then, you could only get $US through the Central Bank and you were only allowed $200US or something around that figure.

So that’s the climate that local designers and The Cloth started in. We did a few shows and then Neal & Massy called us to do their calendar. There were a whole set of designers and we got one month, September, but we ended up on the front page of The Mirror and The Bomb and all kinda ting with that design.

We worked from my mother’s house and played the same song over and over for like a week, Fela Kuti’s “No Agreement.” The whole house was converted into a work studio space – even the living room and the yard – and we presented four groups of clothes which were big statements, big protest things.

We did a garment that became very fad. Fad, fad, fad! The shirt we did was a protest shirt: a bag at the back, like you throw your bag over your shoulder with a belt, right? So the bag was across the back with a stitch onto the shirt at the back. It wasn’t a strap but it was wide, and then there was a placard coming out of the shirt – a three-dimensional placard. It came out and had a statement on it. We showed that, and that thing took off. What they called Ragamuffin came out as a style. Everybody in Trinidad wore bags on their clothes, like sometimes 10 bags, all along their pants, across their shirt. Bag, bag, bag, bag! But like cargo pockets… It was insane! In light blue polyester with pink bags. Madness everywhere! All parties! That was something that people say we generated.

People said The Cloth made them think about designs for a while.

Were they all statement pieces?

ROBERT YOUNG: You could say so. There was Kultur Khronic, we called it because I saw the words on it. It sounded German and I asked a German person who said it was “mad” for “culture” or something. So it was a kinda juxtaposition of things. We took things like Gibson girls’ skirts and connected them with denim flower power from the ‘60s and forced them together. So a big, big full pleated skirt, like a Baptist skirt, and an A-symmetrical denim jacket that was washed in the river, beaten with stones, lino blocked with graphic stuff and pins and all of that, and then with a shirt, all opened. Those were interesting things that we did.

Adele hand-painted things, like historical records… Amerindian images, layered with African images, layered with Indian images, perhaps with a boat over it. A ship, but it was layered.

So it was a shirt from here going this way, stopping halfway at the back, then going a little bit across, and then another one coming from below that, coming from this way, going that way. And then another one on this side came down the neck.

So you didn’t see parts of them, yes?

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes. And you also don’t notice the person’s body. So it would be in voile with at least three layers, and those would be painted gently, nearly looking like inked, antiqued tea stain, and then waxed, and then crackled, and then dyed.

Adele also did some Japanese-influenced kimono things that were like bell bottoms that looked like Japanese Sumarai kudo drummers’ trousers with massive kimono shapes. But we changed the shapes. Instead of rectangles, they were squares: bang, bang, bang, and really big! They were like dragons and tigers, gold painted. They were white with a black bib with gold paintings.

Then we did something called The Bangees, Regardless of What where we did bicycle shorts, referencing Cameo and Janet Jackson’s Nasty video with lino blocked prints.

We had people like Wendell Manwarren and Tony Chow Lin on as models: some were boys from St Mary’s at that period but they were in Chinese Laundry and they were in white bicycle shorts with these T-shirts that were painted. That was also interesting.

And when did you open in the Normandie?

ROBERT YOUNG: 1987. Around that time, the Normandie had Meiling, Claudia Pegus, Craggies, Andre Burke, the Guy James’ brothers… Somebody walked up to us, somebody who didn’t even like us doing the work, and said, “Yer don’t see the shop?” And I said, “What shop?” He said, “There’s a shop opening with Cyprian Thomas and Lorraine Chan.” Lorraine Chan was Catherine Chan’s sister, the artist who did the batchac in Minshall’s “TANTANA.”

So we ended up talking to Lorraine Chan and got into the space. The shop was done in metal pipe, four layers, around the whole shop so you can hang things, but they were painted in lilac, light pink, turquoise blue, aquamarine.

There was also this woman called Heidi Hackshaw with a shop at the corner of Agra Street and Delhi Street in St. James. She only sold local clothes – well, maybe she got one or two things from London, but it was really mostly local. It was a little place where I could sell and get money to pay all my staff because she’d buy everything up. If I dropped stuff on Friday, she’d call and say on Monday, “Robert, they all sell out; you need to come back.” And so I’d bring more stuff at the end of the week or in two weeks’ time, and get enough money to pay all staff just from sales through her.

Was it still the original team at this time?

ROBERT YOUNG: Adele had gone off on her own and Natalie left to study design in London, so it was just me and Camille but we started to do some really interesting things.

We had a polka dot we developed, which was a series of globes with little men in it but the men were always naked with steel tip boots and a little muff and they were inside the circle like in a womb. And they had plugs – like a line with a plug. So, there were these dots with these lines running through the prints, and they looked like they wanted to plug into each other and blow each other up. We would print that first in black and then hand-colour some of the men in pink or green or something, and then put a peace symbol or something on it, so it was always layered like that.

We did a whole series called People Who Came with little stick men masturbating with button heads or button shoulders. There would be buttons on the shoulders like hinges and bows that looked like arrows and their hands would be the prints.

Before The Cloth switched to applique, everything was silk-screened, hand-coloured, waxed, lino-blocked. Always! And we never used print until the other day. Everything was printed – we had to print it – and if we wanted to colour it, we had to dye it.

Every single detail, handmade?

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes. It was basic cotton dyed. And then, we bounced up in electric blue voile. When we couldn’t get that, we did something called Zing Shirts, which were like two layers, like an electric blue shirt with a black shirt over it and we would cut out the details. They would be two separate shirts, tied by the sides, maybe with some buttons but A-symmetrical, so one side would be longer and one side would be shorter.

You said you sketched some things before but I get the sense that it’s when you get the fabric that the real making and idea come together.

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes, but the thinking now and then are two different things.

I have boxes of patterns from the 80s, other patterns from the 90s, 2000, and I’ve not gone into some of these patterns since then.

Like the shirt we did with the big square with the applique: that was in ’87, and it wasn’t an applique. It was…

Hand-painted?

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes, hand-painted. It formed an image of people playing mas on Frederick Street. Really, really happy, and it was just like three or four faces because we had to do Gestetner printing.

So we would take an image, make it small and then blow up this small thing big, so it becomes pixelated.

Instead of taking the big thing and making it bigger, you take the image and you make it small, small, small, and then you take a piece of that, cut it out and then blow that up big, so you would just get a whole cut, like that Obama print.

So, these people were real happy and dancing, right… Black faces. And then above it, we would always have a series of words about Carnival, and sex would always be involved, so there was bacchanal, rum, wine, jamette, condom, sex, hot, sexy. Starlift, Phase II and All Stars had a lot of that, printed above their heads.

We silk-screened that in black first and then hand-coloured it. Or hand-coloured it first and then put an opaque print of black on top of that, and then that would be a square on a shirt. And sometimes, we’d do all three things: silk-screen, hand-colour, batik, wax, dye.

But then we also had a shirt called the TV Shirt, which was a basic square shirt with a hole cut out the size of a screen. We’d face that thing that we cut out so that it would be smaller than the spot that it was in, then put it back with a piece of cloth in red at the bottom, like the speaker, side panels and something at the top. So you’d have spaces where skin would show, some inlay, some knobs and space for a statement. It was really very simple, very matter-of-fact.

In 91, we had the Window Shirt. It was a shirt where, instead of putting the applique at the front, we put it to the back as a window, and then we would play with opaque whites and light whites, cotton and voile. We would mix them and you would be getting half of a shirt with voile and then the other piece was heavy.

And then there was the Temple Shirt, which we used a lot. The shirt would have a cutout like a temple shaped thing, and inside the pocket there would be something like those Welt pockets that you would have at the back of your pants. So there would be a slit where there would actually be a pocket, but you would see a temple and it would all be done in voile so you would get these nice layers that were almost architectural.

The point is that the thinking continues to change.

So, which is more important – the statement or the design?

ROBERT YOUNG: The statement! Because I never wanted to be a fashion designer.

What’s next for The Cloth?

ROBERT YOUNG: What we’ve been working on is the idea of a thanksgiving, which is something I have been working on for a while now, from the old Orisha things. We’re going to pay attention to the classic cloth and we’ll see if we can get back into print and all the other possibilities beyond appliques.

But the first thing we’re going to do is applique classics and ensure that classic cloth is available in every major place in the region. That is a plan I’ve been working on to be completed soon, so I hope when it comes out, there would be some sign of that.

thecloth.com is something that we’ve been watching since the late 2000s and played around with so we’re trying to establish our online presence. Right now, theclothcaribbean.com is a strong site in the sense of a historical place where you can go in and find things. A lot of people come and say, “Well, I’ve been trying to find this since the 90s. I don’t know where to find it.” This is where you find it.

You know, you said that you never wanted to be a fashion designer, but you still made the choice…

ROBERT YOUNG: …to do fashion. I think, retrospectively, the only reason I kinda stayed with it was because it was the only thing I did that people really seemed to really appreciate. Because, other than that, they thought he’s too mad, he’s too different, he’s too late, too erratic, too whatever, whatever, whatever!

If I look at my own life, I’ve been committed to this. I’ve stayed with it. Because there are things that we do well. The Cloth speaks and the talks at propaganda… I think back on a talk that started off with a psychologist talking about the colonization of the mind: Chris Cozier was talking about it and Sean Leonard was talking about it with architecture, but it never came out. I thought it sounded like a symposium because they were talking about months of months of work

Lloyd Best said, “What needs to happen, needs to happen badly.”

And that was in both senses: it urgently needs to happen and, if it happens badly, it’s okay, because it happened. If you wait for it to be done well, it’s not be going to be done at all. I’ve always said that work expands or contracts for the space provided for its completion.

I remember reading a book on campus by Paula Morgan called Caribbean Studies, or Caribbean something. She has an article called Pan Caribbean World, by CLR James, that describes the region, not just these islands but anything touching the water. So Miami is the Caribbean. Mexico, Costa Rica, Belize, Guatemala, Venezuela and Columbia are the Caribbean. What if that was taken on as a project of trade and design and sharing – cultural exchange and all of that – we have our own thing. Because, you would go into those places, even Costa Rica and Panama, and some people talking Jamaica because they went there in 1914 when they were building the Panama Canal and they didn’t go back home.

Speaking of home, what was your home life like?

ROBERT YOUNG: My father was a trade unionist who never really… I think my fascination with him is that he never really lived. I think when I was born or conceived, that is the time that he led his trade union – ‘64 to ‘79 – and he was absent. He just visited.

There are stories… my mother said I would hold on to his leg dragging when he was leaving the house. So that’s my fascination with that truck outside – the Land Rover – because that was his own. People said he was the most militant trade unionist in Trinidad. I have pictures somewhere with “Stop the PNM Dictatorship” – a conference that happened in the union hall. There were massive pictures of Che and Castro and Lenin and I heard people say that CAFRA (Caribbean Association for Feminist Research and Action) was birthed there, got support in that trade union TIWU.

They had a few groups, working women with Jackie Burgess and dey, but there was also CAFRA which was a big, big feminist organisation that was funded from outside but did a lot of work and research. They pushed to get the Rape and Marriage Bill passed.

So all those things happening and bubbling around the place. Happening, happening, happening, happening!

There was a Caribbean sports day or cultural exchange on campus. We couldn’t go to Carifesta, because we were too poor to go, but seeing Jamaicans in ‘73 dancing to Bob Marley and seeing things like Calabash Alley and significant plays being done on campus in the night as a young person… Going to see my aunt’s – Jean Coggins – dance troupe… In ’72 she did the first and must be the only African folk ballet, Waiting on Erzulie. Going to Queen’s Hall, we reached late, and seeing this thing in Queen’s Hall in ’72, seeing that kinda big fascination in a way that could just blow your mind. Also, beginning a fashion show at Daaga Hall on campus in ’70, wearing daishikis and waistcoats with fringes, like the Jackson’s, with puff sleeves, and afros with my mother.

It was just three of us. My younger brother wasn’t born yet, so we would be out with these leather waistcoats with fringes, brightly coloured shirts and bell-bottomed pants, or we’d have a reversible shirt or daishikis, one side with one print and the next side with another print. And we began a fashion show at Daaga Hall, coming off the stage to change the dashikis on the next side to come back on.

And then, my brother – one of my father’s first sons, Curtis – was a tailor. We used to have to go and wait for trousers, or school pants or something. That was on Green Corner and Tragarete Road. And having in my mind, if I failed through school, I would do this.

And I used to say,

“If I fail this, I’m going to be a priest.”

From fashion to priesthood?!

ROBERT YOUNG: I used to say that priest business is the best wok because you’ll get people to believe you, you’ll have a doctrine that is 2000 years old behind you, you get a free car, you get a building and, as an Anglican, you can marry. You could live around the Savannah if you were a good priest – a bishop –in Haynes Court. So that is where The Cloth – the priest and man of the cloth – came out.

INTERESTINg!

ROBERT YOUNG: Yes! So, the story is always first, or the justification of the story. The thanksgiving, that is his clothes: you’ll have to have three good pants, you’ll have to have four good skirts, you’ll have to have three good blouses, five good dresses, two good jackets – one male jacket and one female jacket – one long dress, one big piece that is ending. So you frame it like that, and you might be drawing all the time… And I’ve not drawn for a while, but things will happen, I suspect because I’m looking all the time.

So you draw, draw, draw, draw, draw! I sit down and draw, draw, draw, draw files of drawings I’ve never made. Draw, draw, draw, draw, draw! And then you have to pull to fill these five shirts in the story. The story that you have that you’ve made, these things have to fit into the story.

What do you think ‘fits’ into the Robert Young story?

ROBERT YOUNG: Congolese, Bantu, Ghanaian, Nigerian, Iranian, Peninsular and Portuguese ancestry. I’m 26% Irish, 2% British, 3% Jew, 1% South Asian, and from like 16 places in Africa. I was at a workshop with my sister the other day and the leader was talking about how people are saying they just want to be White or Black, Caribbean or Trinidadian. They don’t want to bother with ancestry and all that. My sister said that’s a very short way to think. You have a lineage and you have to know what it is.

Your life would be better if you know what soil you came from.

You have to go and visit all your soil.

You have to, and if you have to grieve it, grieve that those people were your people,

you have to do it, because it doesn’t make sense to be living and saying you’re just Caribbean. It’s shortsighted. It shows you don’t want to touch the difficult history, you don’t want to touch the pain…

I found out something the other day where somebody wrote something about White people and Whiteness. Whiteness is a comfort space: it gives you a kinda neutrality. But before you were White, you were something else. You were German, Polish, French, even from a tribal group who would have had songs, jewellery, crafting, clothes, ways of making food, and you drop all that to eat a hamburger and now you’re tied up in, “My culture is boring.” …

So, what are you?

ROBERT YOUNG: I’m a person who comes from a place where my future is also determined by my limitations and my patterns. They say that you were sent here with a shopping list, that you have a thing to do here, so I’m also an artist. And my art, The Cloth, is transforming.

INTERVIEWER: TANYA MARIE PHOTOGRAPHER: MARLON JAMES