JUNE, 2025

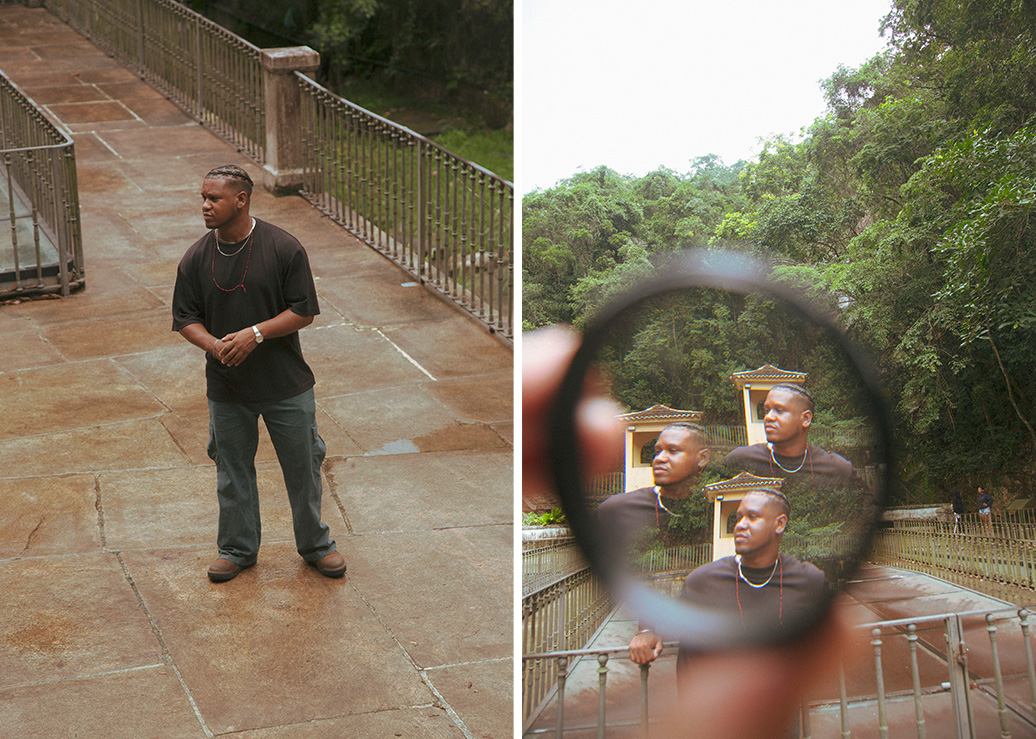

By the time you read this, Adam Cooper would have already packed his bags for his next assignment.

Though, by his own measure, he’s almost always away from home wherever he lands, for a man perpetually known as foreigner, Port-of-Spain is where the new year begins.

A multi-hyphenate in an increasingly deep sea of them, Cooper’s cross-cultural group hug continues into Carnival, and in the part of the festival he totes in his carry-on.

Even away from Trinidad and Tobago, Cooper references what’s at home, both contemplatively as a position on the planet, and in out-loud musings of sound, colour, powder made manifest in his Junkyard Jouvert series.

In our creole, Cooper recognizes a mechanism for collective liberation, his resulting gregariousness is his innate reflex to add to the dialogue.

Slowly occurring during two Trinidad Carnivals and after his first in Brazil, our conversation with baby griot aka droney matterhorn surrounds thoughts on culture, identity, and the power of being present, even while revelling in constant displacement.

Tell me who you are and what you do?

Foreigner: My name is Adam Cooper, most people know me as Foreigner. I work primarily in event production and cultural programming; Centering Afro Trinidadian culture, centering Afro Caribbean culture out of Los Angeles, and from that work I have been able to travel, DJ around the world, and bring the culture to people.

Why do you think our music is so important to spread and evangelize just like your pops would have?

Foreigner: I think on multiple levels, just thinking about the story of steelpan, and how there is such ingenuity in its development coming out of oppression, coming out of the stifling of cultural expression through drums, through percussion. The steelpan was born out of constraint, and I think that story runs parallel to a lot of different parts of the diaspora.Of course, the Haiti Revolution, as Atillah Springer says, the first jouvert was Bois Caïman; the struggle in West Africa, the African American struggle there is a lot of ingenuity that comes out of Blackness because of the constraint that we have and demonstrating that there is strong correlation between, for instance, Afro House and Laventille Rhythm Section… to Trinis or to people in the Caribbean that’s basic arithmetic: 1 plus 1 equals 2. To a lot of people out in the diaspora, that might not make sense.

So my efforts are to bring that correlation to the fore in ways that make sense, in ways that are accessible and not over-intellectualized. That’s what I really enjoy doing.

You carried Laventille to L.A. the other day right?

Foreigner: (laughs) Yeah, the other day as in 2017! That was amazing. I had an opportunity when Red Bull approached my colleagues and I to curate the opening event for their festival in Los Angeles in 2017, and they gave us carte blanche. They were like, Hey what ideas do you have?’ and each of us came with a list of ideas. The first idea that came to mind for me was “yo let’s bring up Laventille Rhythm section to LA” and they were just like “okay.” So we brought up 12 of the gang and it was their first performance in the US. I really didn’t know how Los Angeles would react to a Trinidadian rhythm section, but we mic’d them up and it was the highlight of the night.

I shed a tear that night. It was like “We here!”

Los Angeles is a city where a lot of decisions in the entertainment industry are made, so for raw Trinidadian culture like Laventille Rhythm Section to serve as a reference in the city was very important to me. Major milestone for me.

How does it feel being home?

Foreigner: Trinidad for me is a very reflective place. It doesn’t matter what my agenda is. I can come with tickets for every fete, I can have a costume in whatever band, but as soon as I land in Trinidad, as soon as I land in the place where I was born, I go inwards.

Instead of just staying here just for that carnival period where there is incessant pump, I am staying until the end of March (2024) to really listen to myself while I am here, and see what comes about in terms of what I can make, who I can connect with, what I can document.

At the end of the day, the work that I do of course manifests through events, but it is really storytelling.

It’s really about telling people the stories about how we are really connected as Black people across different borders and waters.

Random: What’s going on here?

Foreigner: Ay! what’s going on, you good, we’re talking about what it’s like to come back to Trinidad while you’re away so I’m just giving him that anecdote.

It’s at this point the first part of our conversation gets interrupted, more than a year ago, by a voice identified as ‘Random’ by my ol’ faithful transcriber.

The meeting isn’t random; alongside our conversation’s audio is a constant drum and bass drone from the speakers in William McIntosh’s backyard.

Foreigner and fellow returnee from up north, New York-based DJ Gabsoul played sets under the sprawling canopy behind McIntosh’s Curepe homestead.

There Backyard Bonfire, a beat-driven, community cultural action, has served as a tinder box for creative expression in recent years.

“Let me just say something real quick,” Cooper reinterrupts “last year (2023) I came to Trinidad, not with a big plan, not with a big itinerary, but Gabsoul was performing at Backyard Bonfire so I pulled up.

“And these fellas have built out a space that I wish I had when I lived in Trinidad. I lived in Trinidad until I was five years old then I moved back between 24 to 28. When I was here those years in my 20s there was nothing like what they have going on here.”

“Jouvert was the perfect starting point because it embodies the raw essence of soca music, carnival, emancipation and freedom. – It’s where the joy, chaos, and defiance of Carnival began, making it a powerful and authentic gateway to our culture as Trinbagonian people in a city like Los Angeles.

“

…

Cooper is back in present-day Trinidad and we again get back into it.

What about your own build up that makes it so multi-cultural the way that you produce, the way that you listen to and hear music?

Foreigner: Well I mean the way I was raised, I am unable to ignore Pan-Africanism. I am indebted to my country.

I am always indebted to Trinidad and Tobago. I always try to bring money back, always try to rely on the culture, always try to create opportunities for Trinidadian artistes, entrepreneurs, and Trinidadian people in general.

But I am a Pan-Africanist at heart, so any opportunity I have to demonstrate that there is rhythm that really does run parallel to each other from all over the diaspora, I will always take that opportunity because at the end of the day. The strongest modern day manifestation of Pan-Africanism is through music.

Tell me about your family and its history and how steelpan became so important to you and in your life.

Foreigner: My father’s name is Michael Cooper. His company, Panland, manufactures arguably the highest quality steelpans you can get.

The factory is in Laventille. He left his career as an electrical engineer in the corporate world to dedicate his life to evangelising the national instrument. From his work, I‘ve been able to earn my degree. My education was paid for by the music, the work my father does.

He set me up in a way to succeed, and in turn I owe my education and my position in life to steelpan. Thus owing my position in life to Trinidad and Tobago.

There are others all over the world with pop-up Trini vibes—how does yours differ, and why did you choose Jouvert as an introduction to the culture?

Foreigner: What I think makes my approach unique is that I prioritize creating immersive experiences driven by nuanced and opinionated storytelling.

I always say that it’s a practice, not a product. So while it’s definitely about a really really really good time, it’s also about crafting a story that connects us to the deeper history and significance of the culture.

Jouvert was the perfect starting point because it embodies the raw essence of soca music, carnival, emancipation and freedom.

It’s where the joy, chaos, and defiance of Carnival began, making it a powerful and authentic gateway to our culture as Trinbagonian people in a city like Los Angeles.

As someone who seems engrossed in unity, how do the present fractious times find you, and has it inspired you to press on?

Foreigner: These times are deeply challenging, but they’ve also reinforced the need to create spaces where people feel seen, connected, and empowered.

Unity is a necessity for survival, especially as it pertains to class solidarity and diasporic communities.

The madness of the times inspires me to double down on my work because — as the diaspora wars continue to flare up online — every event, every project, is a small step toward bridging divides and reminding us of the strength we have together and how our ancestors have already done what we aspire to achieve.

Is the Carnival you’ve come to know helping power the kind of awareness in which it’s rooted?

Foreigner: Carnival is a powerful platform, but I think its potential as a tool for sociopolitical awareness can still grow.

While it celebrates emancipation and cultural resilience, overcommercialization and hyper-premiumization (yes I made this word up) sometimes overshadows its roots.

We have a responsibility to balance Carnival’s spectrum across tourism products and cultural programming around the world in order to keep the narratives of liberation and unity alive through the way we celebrate and share its stories.

From your perspective as someone who also seeks out other cultural phenomena, how can our own forms of expression remain rooted while innovating?

Foreigner: Innovation thrives on understanding history. Innovation thrives on Sankofa.

By staying rooted in the stories, traditions, and values that define us, we can build upon them with fresh ideas and new media.

For me, it’s about merging the past and present—honoring the ancestors while creating something they’d be challenged by.

How often do you find commonalities in the diaspora?

Foreigner: Every single day. The connections across the diaspora are both subtle and profound, from the rhythms in our music to the ways we celebrate freedom and community.

Whether it’s a Carnival, a block party, or Afrobeat set in a different corner of the world, I often find that the underlying spirit of resistance, joy, and creativity is universal.

What stop has felt more like home than the others?

Foreigner: No where really feels like home. Not even Trinidad.

Every where I go, I’m constantly reminded that I am a foreigner.

While it sounds depressing, it is actually quite the opposite — being a foreigner every where I go has led to people extending the most intentional hospitality, thus making everywhere feel like a foreign-but-familiar branch of the diaspora.

“It’s about staying connected to the bigger picture and contributing to it in meaningful ways. “

You’ve invited your friends along this time—why do you think it’s important to bring them to the source?

Foreigner: I’ve spent years emulating our culture in Los Angeles, now it’s time to bring friends to the source.

It’s one thing to experience the culture secondhand through parties or music abroad, but it’s transformative to witness it in its birthplace, where every sound, color, and movement carries centuries of spirituality, history and pride.

What are some of the other creative projects that have occupied your time?

Foreigner: Recently, I’ve been really interested in more intimate travel and hospitality experiences.

I’m currently working on Hyfen, a creative retreat platform focused on connecting like-minded individuals in dynamic settings, as well as developing Roadblock Night Market, which blends Afro-Caribbean food, music, and culture.

I’m also exploring filmmaking as a way to tell stories that resonate across the diaspora.

How do you sustain a creative outlook on life?

Foreigner: By staying very clear on my emotional state, by remaining curious and engaged with the world around me and my peers.

I draw most of my inspiration from traveling, music, art, and conversations with others, but it’s the internal conversations with myself about my mental state, my emotional intelligence, and my role in the bigger cultural picture that keep me pushing the creative limits of what we do.

What motivates you to continue experiencing the world in the way you do?

Foreigner: The belief that there’s always more to learn, feel, and create. Every experience adds a new layer to my understanding of myself, the cultures and the people I engage with.

It’s about staying connected to the bigger picture and contributing to it in meaningful ways.

What’s after Trinidad and Tobago Carnival?

Foreigner: This year the plan is to skip Carnival in Trinidad and go to Salvador, Brazil for its own take on Carnival.

It aches me to leave because I know Carnival in Trinidad this year is going to be madness, but in order to really be a student of this Carnival thing, I need to dive deeper into the ways Black people celebrate around the world. Salvador is the cradle of Brazilian culture, and it is the Blackest city outside of Africa, so tapping in with Afro-Brazilian Carnival culture in Salvador will be a real dive into the way they celebrate freedom and resistance.

Beyond that, I’ll continue building on my creative projects, especially the 2025 iteration of Junkyard Jouvert.

Still basking in a first experience worlds away from his formative festival, foreigner’s dispatch from Salvador reads like the love letters we try to compose about ours these days.

Wistful, festooned with memory, a recollection like those composed of bass, brass and timbre held in the opening twenty-nine seconds of Shadow’s Stranger and the comment that unfolds over the rest of its five minutes and thirty-one seconds.

His experience confirms what David Rudder intimated in the book Kaiso, Calypso Music (New Beacon, London. Port-of-Spain, 1990) an adaptation of a conversation with John La Rose at the National Sound Archive on Thursday October 8th, 1987.

Rudder says “…as a matter of fact ‘Bahia Girl’ was a song about our common link because many people didn’t know about Bahia in Trinidad…

“I tried to show that despite the Middle Passage, in spite of the separation, that common thread still travels through us all. The girl was actually a symbol of that thread, she wasn’t a real person you know, as people thought.

“She was just like a messenger, saying, well, all is not lost, that thread is still there…”

Foreigner: Summer 1999, a year after moving to the U.S. from Caracas, my brother, my mother, and I landed in Brooklyn with nothing. No money. No papers. Nothing. We didn’t belong.

My mom took a job in New Jersey that summer, leaving my brother and me with distant relatives on Troy Ave and Sterling Place. The house — a classic Crown Heights row house belonging to our distant Gasparillo relatives: the Raphaels. It was ram. Upstairs, three bedrooms: Uncle KD and Aunty Desre, Sasha and Kamilah, and one bunk bed room for Lindsay, my brother, and me. The second floor had four more rooms for Uncle Hugh, Aunty Sharon, Hugh J, Sabrina and Diane. The ground floor had a kitchen, living room, and a backyard merged into a pan yard for Sonatas Steel Orchestra. My cousins from Florida, Punjee and Kenya, were also there that summer. We’d never met our Gasparillo family before, but family is family.

The house was too ram. The house was too hot. Too hot to sleep. Too hot to think. Too hot in the literal. Too hot in the figurative. AC only in the master bedrooms. Pan beating day and night, soca running night and day. The block didn’t sleep, and neither did we.

My brother and I from Venezuela, Punji and Kenya from Broward, the rest Brooklyn Trinis — but we all spoke the same language. We had the same timing. Our clocks synchronized, counting down to madness on the Parkway for Labor Day 1999. Every day, every night, we laughed, danced, cussed, misbehaved, ate, drank, and lived. The intimacy was instant.

We were far from home and life was far from familiar, but family is family and vibes is vibes.

I haven’t felt happiness like that since.

That is Carnival in Salvador for a Trini.

Carnival as Liberation & Protection

Carnival in Trinidad is Carnival in Salvador. Carnival in Salvador is Carnival in Trinidad. It is the same consistency of joy, the same release that brings tears to your eyes and strength to your soul. It is a spiritual barrier that’s our birthright—a shield we recharge every year to navigate the f*ckery and the oppressive climates of our worlds whether in Trinidad, Brazil, Los Angeles, or London. It’s not just a mad jam; it’s part of a nutritious diet passed down to us. It’s a gift that must be protected from the money grabbers and culture vultures. A gift we have to make sure remains in the hands of the people.

The People’s Carnival vs. The Tourist’s Carnival

The big difference between Salvador and Trinidad? Ownership. Salvador’s Carnival started off as deeply elitist but transformed into a massive, city-wide, unapologetically accessible festival. While there are many options for a luxury Carnival experience in Salvador that run parallel to Trinidad’s vibes (camarotes), free public programming feels safe, premium, immersive, and spiritual — happening everywhere, all the time for weeks on end. Carnival in Salvador — the Blackest city in the world outside of Africa — is passionately and aggressively African with the music and movement feeling like a baptism, a renewal, a reminder that our ancestry is powerful and we must honor it with every breath we take.

But police presence in Salvador? Mad loud. Mad militarized. Mad scary. When they walk, people freeze, make way, and warn everyone. They’re considered the most brutal in Brazil. I learned this the hard way after collecting three baton lashes for jumping up a little too wild.

Trinidad’s Carnival has my heart. Nothing compares to our fetes, mas, music, and artistry. It’s where my parents’ romance first sparked; it’s part of my DNA. But I’d be lying if I didn’t say parts of it have become overly commodified and the soulfulness is leaking. The most popular experiences cater to those who are willing to pay top dollar, top euro, top pound. Free, safe, accessible, premium-feeling public programming? Barely exists. It’s storm, pay or beg for the comp. I hope — I pray — that one day we reject elitism in Carnival in the ways Salvador has (even though Salvador faces racial stratification and absurd systemic subjugation within and beyond Carnival). At least, unlike Salvador, the chance of getting brutalized by police is lower.

There’s a hunger for authenticity. That’s why Pan is alive with youth. That’s why people fly to Salvador to feel the power of Olodum and chant anthems. That’s why the popularity of Kambule and Kalinda continue to grow each year. So, how do we build a sisterhood between Port of Spain and Salvador? How do we make Carnival more accessible in T&T? How do we share pan, kalinda, jouvert, and soca with our Bahian cousins? How do we amplify our roots as Carnival’s crown jewel?

Intensity, Chaos & Uncontainable Blackness

If you wonder what Trinidad Carnival felt like before cell phones, go to Salvador. Phones aren’t banned, but it will get stolen if it’s in your hands. swiftly. The result? Presence. Pure presence across the sea of people on the road.

The streets are ram. There’s only room to dance — elbow to elbow, waist to waist. It’s a wild, joyful mosh pit to the sounds of Axé and Pagodão Baiano. Pagodão hits like soca — sometimes groovy, sometimes pure power.

Like Trinidad, Salvador’s Carnival is relentless — hot days blur into hot nights. Trinidad pulses with the hot, intimate exchange of a wine or two. Salvador is a sea of bodies, sweat, and a Brazilian heat that explodes into passionate tongue kissing between total strangers. And no matter how commercialized or policed, the raw, uncontainable Blackness of Carnival remains untouched. It cannot be buffed out, it cannot be erased, it cannot be packaged.

Carnival in Trinidad is Carnival in Salvador. Carnival in Salvador is Carnival in Trinidad.

Interviewer: Jovan Ravello | ILLUSTRATION BY: Tanya Marie | Photographers: Image 1 & 2 by V. Debeija, image 3 by Harold M.